Over a third of working women worldwide are employed in agriculture and food systems, playing a critical role in global food security, health, and nutrition. Despite this, female farmers receive less than 10% of agricultural loans, a persistent barrier to gender equality in agrifood systems. This is compounded in smallholder communities with patrilineal inheritance structures that can prevent women from owning land, depriving them of the security and decision-making power that comes with ownership. “Men have the luxury to move from one fertile land to another. Women are left and either given land that is not fertile or no land at all,” says Salma Abdulai, Co-Founder of Amaati, one of the twelve agribusinesses owned or led by women supported by the Connector program.

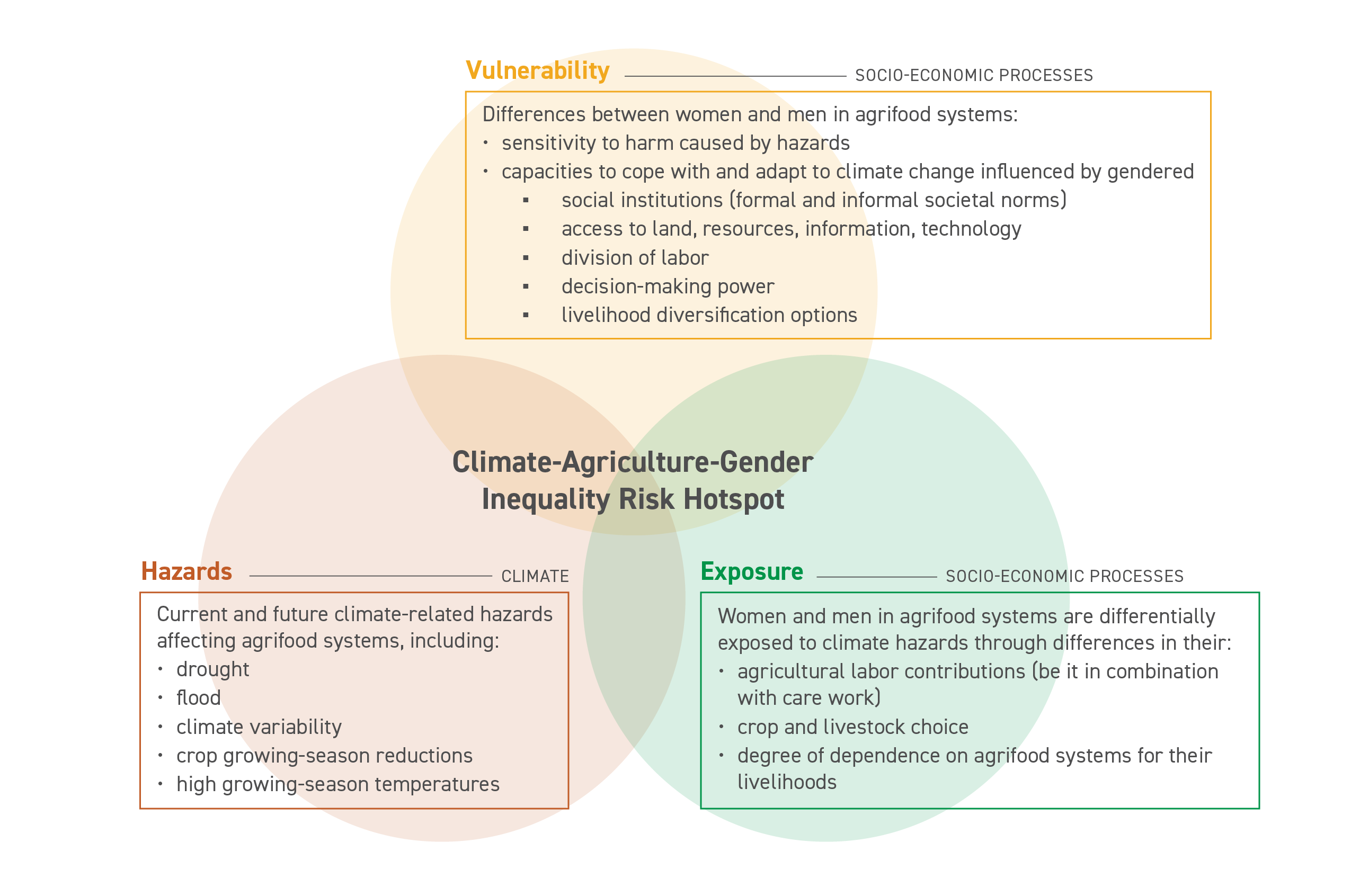

Climate change is exacerbating the situation. Droughts, floods, and heatwaves are intensifying, pummelling farm yields and incomes worldwide. The outmigration of men to urban areas in search of alternative employment has become more common, especially in degraded lands. This leaves women to fill the gap, despite having less access to agricultural land, financing, services, and technology. “Women farmers form the backbone of Nigeria’s agricultural sector, yet they are still expected to farm without the tools, inputs, or support systems that men can access,” shares Eneotse Isosie Unoogwu, Founder and CEO of AlltimeFresh, also supported by the Connector. As a result, women are disproportionately vulnerable to the impacts of climate shocks and the economic losses they trigger.

“Women farmers form the backbone of Nigeria’s agricultural sector, yet they are still expected to farm without the tools, inputs, or support systems that men can access,” shares Eneotse Isosie Unoogwu, Founder and CEO of AlltimeFresh, an agribusiness supported by the Connector.

Women farmers are disproportionately vulnerable to the impacts of climate shocks and the economic losses they trigger. Source: Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2023

With women comprising over half the agricultural workforce in major agrarian economies in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, closing the gender credit gap is a critical driver for sustainable economic development and climate-resilient food systems. Agribusinesses like Amaati and AlltimeFresh are innovating ways to centre women and climate in their models, for economic, environmental, and social benefit. “We integrate a gender lens into our selection because it makes for better, more stable businesses, and acts as a force multiplier for climate resilience,” says Wen E Chin, Manager of the Connector.

A crop for women

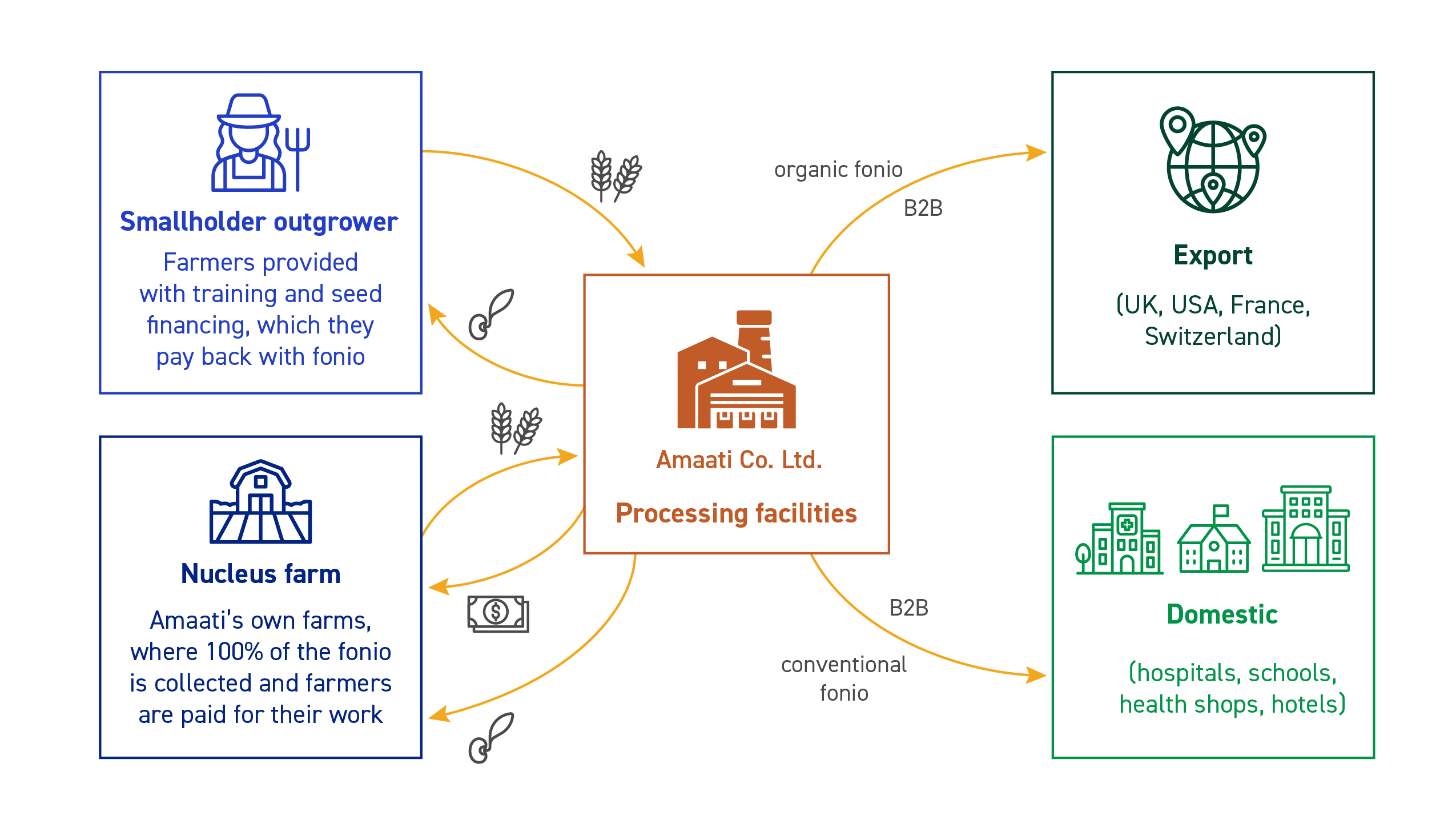

Amaati facilitates women’s access to marginal lands to grow fonio, a climate-adaptive and nutrient-dense grain indigenous to the West African savannah. The idea to cultivate fonio came to Salma during her Master's in Agricultural Economics, when a lecturer spoke about farmers growing fonio in mountainous, rocky regions of Guinea. It occurred to Salma that fonio should be increasingly used in Ghana, where abandoned lands are abundant in the North.

Since then, Amaati has trained and provided seed financing and mechanization services to over 11,000 female farmers. Fonio is the ideal low-maintenance, low-cost crop: it doesn’t require fertilizers or pesticides, and it is both drought- and flood-tolerant. The appeal was clear to Salma. “We don’t need a crop that will add another burden on women. Climate-friendly crops would at least help reduce the pressure that already comes with farming,” she explains. The crop’s climate resilience was critical for adoption. As droughts become more common, water-intensive crops can fail, increasing debt burdens.

“We don’t need a crop that will add another burden on women. Climate-friendly crops would at least help reduce the pressure that already comes with farming,” explains Salma Abdulai, Co-Founder of Amaati.

Amaati offtakes the grain to be processed into flour, cereal, or bran, for export and domestic markets. As fonio is typically cultivated during the monsoon, Amaati has recently begun to engage women during the dry season by encouraging them to harvest African locust tree beans. The pulp of these beans, usually discarded in favour of the seed, can be mixed with fonio flour to create a gluten- and sugar-free biscuit. Salma notes that during the drier months, the women engage in woodcutting for charcoal burning as a source of income. “We think that if they leave the trees and don’t cut them down, they can make equal money,” she tells us. She suggests that this can lead to the long-term preservation of the locust bean trees, a positive for both women’s incomes and climate mitigation.

Amaati facilitates women’s access to marginal lands to grow fonio, a climate-adaptive and nutrient-dense grain indigenous to the West African savannah.

A fresh take

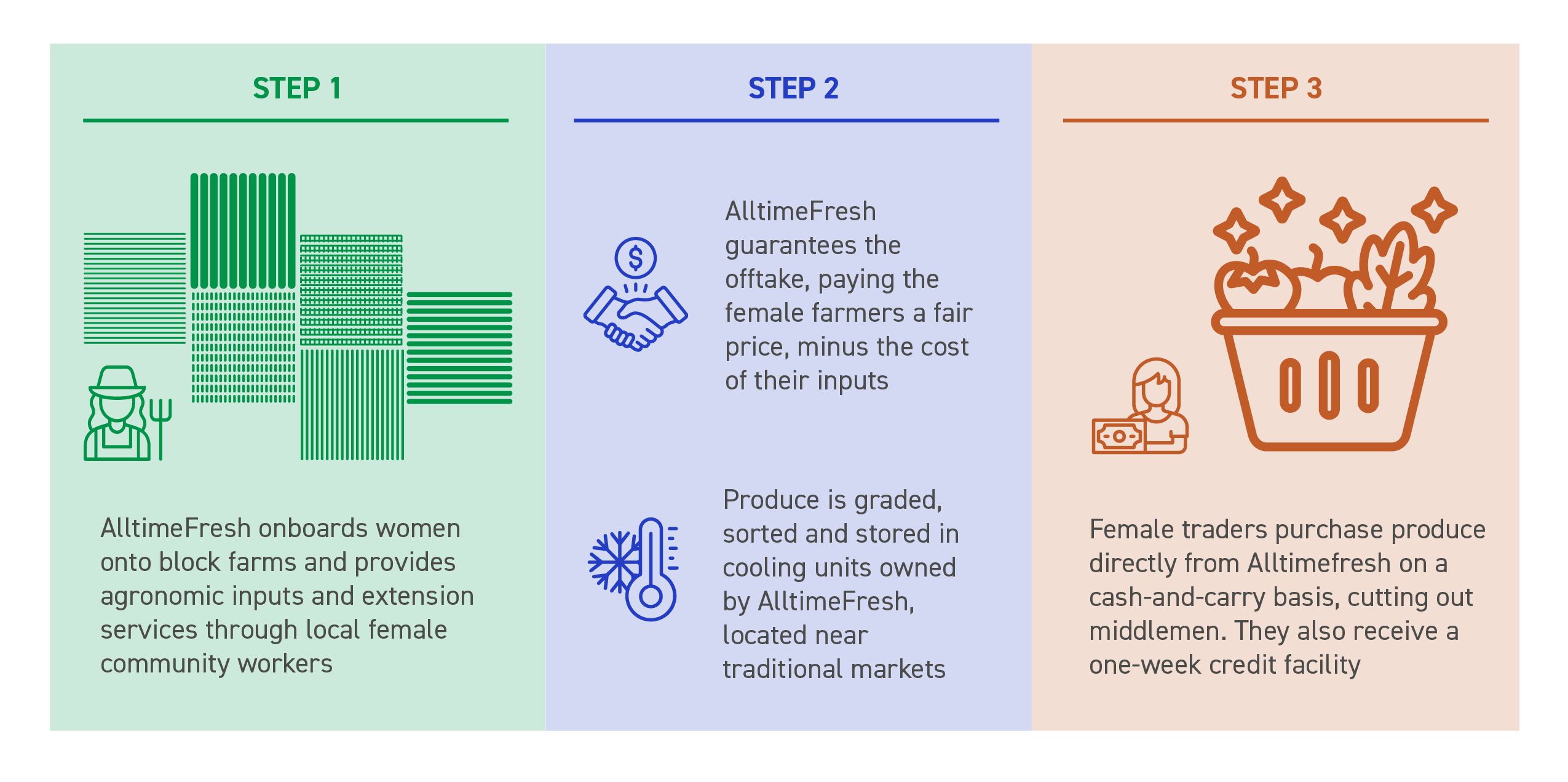

Using a unique collective model, AlltimeFresh brings female farmers in Nigeria together on shared “block farms,” large tracts of land combined to eliminate physical boundaries. This increases economies of scale for women who are otherwise engaged in small-scale vegetable farming or trapped in other low-income, informal activities. Each of the block farms has a local female community worker who Alltimefresh trains in climate-smart agronomy. The community worker, in turn, supports farmers in implementing practices such as using drought-resistant seeds, bio-inputs, and solar irrigation, resulting in 100% on-farm adoption. As a result of these enhanced practices, Eneotse is seeing yields that are five times the average.

The climate impacts don't stop on the farm. Further downstream, the company operates six solar-powered cold storage facilities near local farmers' markets. From these facilities, the company supplies fresh produce to over 3,000 female traders operating in traditional, open-air markets, where 72% of Nigeria’s agricultural produce is sold. Preserving farm harvests is critical to Nigeria’s food security and climate mitigation, as approximately 50% of fresh produce is lost to heat spoilage from inadequate storage and transportation.

Alltimefresh sells produce from its block farms to female traders on short-term credit, allowing them to align payments with their sales cycles. “We want to go cashless,” says Eneotse, sharing her hope to partner with fintech companies in the future to ensure all the women employed by them are banked and have autonomy over how their earnings are spent.

AlltimeFresh's shared block farms increase economies of scale for female farmers in Nigeria who otherwise engage in small-scale vegetable farming or are trapped in other low-income, informal activities.

Looking through a new lens

When asked about the returns on investing in women, Salma shares that Amaati benefits from a committed workforce that delivers consistent, high-quality fonio. “Most women use [their profits] to pay their children’s school fees, so they call us ahead of time to ensure their fonio is collected promptly,” she says, resulting in a reliable, scalable supply for her company. As part of its efforts to strengthen community resilience, Amaati provides health insurance to its employees and has helped establish a Village Savings and Loans Association (VSLA). Salma’s co-founder, Abdulai A. Dasana, points to Amaati’s vanishing default rate on input financing as evidence that their model is working.

Evidence from investors corroborates the value of dual lens investing or applying two different perspectives of gender and climate into agrifood investment decisions. CLIC member Root Capital, which has invested in over 120 gender-inclusive and women-led agribusinesses, analyzed 10 years of data on USD 1 billion of its loans across Africa, Latin America, and Asia. The findings were clear: businesses with higher levels of women's leadership or participation had more stable revenues, grew faster, and defaulted on their loans less frequently. They were also more likely to acquire new sources of financing and yielded dramatically higher profits on their loans.

Root Capital's findings were clear: businesses with higher levels of women's leadership or participation had more stable revenues, grew faster, and defaulted on their loans less frequently.

Elizabeth Teague, Senior Director for Climate Resilience at Root Capital, highlights that while financial innovation can help mobilize more capital for dual lens investing, there is still a need to make existing structures work for women. “It’s about changing the structural conditions to make sure finance is flowing to the right place,” she explains, sharing an example of Root Capital’s work with cooperative internal credit funds, “where many policies that are thought to be gender-blind are effectively excluding women, because they set too high a bar in terms of size of land or other conditions required to access financing.” Root Capital saw an opportunity here to support existing cooperative lending programs by providing gender equity advisory services.

Leonor Gutiérrez, Director of the Women in Agriculture Initiative (WAI) at Root Capital, suggests applying the dual lens by segregating client data performance by gender, so that trends are easily visible. For instance, the 2X Global Climate Finance Taskforce finds that enabling women to access resources to the same extent as men can increase on-farm yields by 20 to 30 per cent, leading to better business outcomes for companies and investors. For agribusinesses, Leonor’s advice is to “search for other women involved in the agribusiness to elevate their leadership, who will show up in trainings and conversations.” This both prevents the burden of representation from falling on one woman and ensures that a new generation of women is trained to lead the way forward in inclusive, climate-positive agribusinesses. As Salma puts it, “We cannot fight the culture that has been in existence for more than centuries. We only need to build something different and unique to make it obsolete.”

Most importantly, Leonor adds, we need to ensure that gender equity is “not a side project.” Eneotse too emphasizes the importance of being committed to the process. “You can’t just walk into any community and say you want to empower women,” she explains. She spends time engaging community leaders, conducting house visits, and speaking with the husbands of female farmers to secure their support. This has made her work more effective and enabled women to achieve economic freedom and financial agency in situations where they were previously dependent on men’s allowances. She concludes, “Women take what they do seriously. When they are given the opportunity, they maximize it.”